4. Lenses

4.1. Conjugate Equation

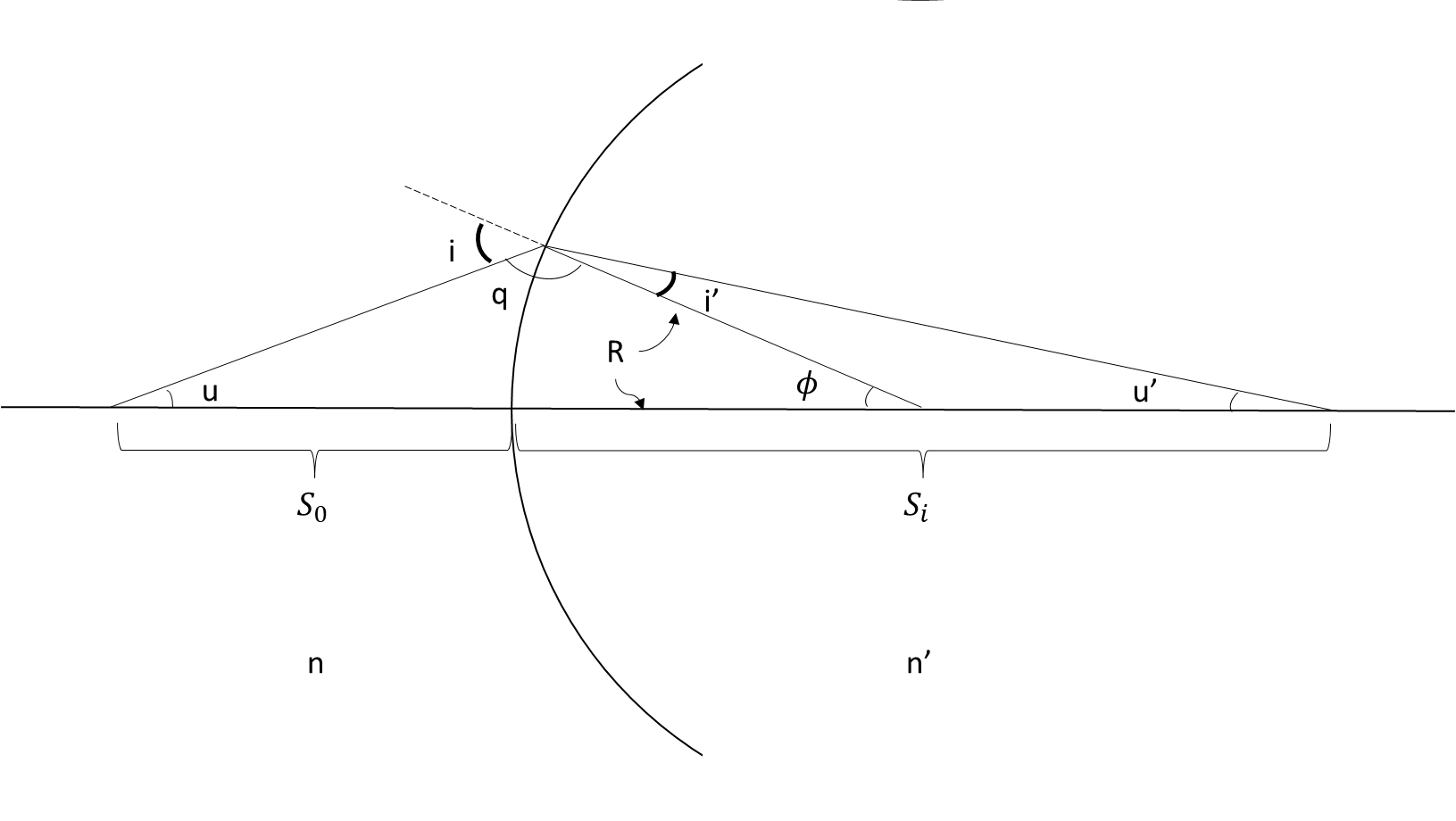

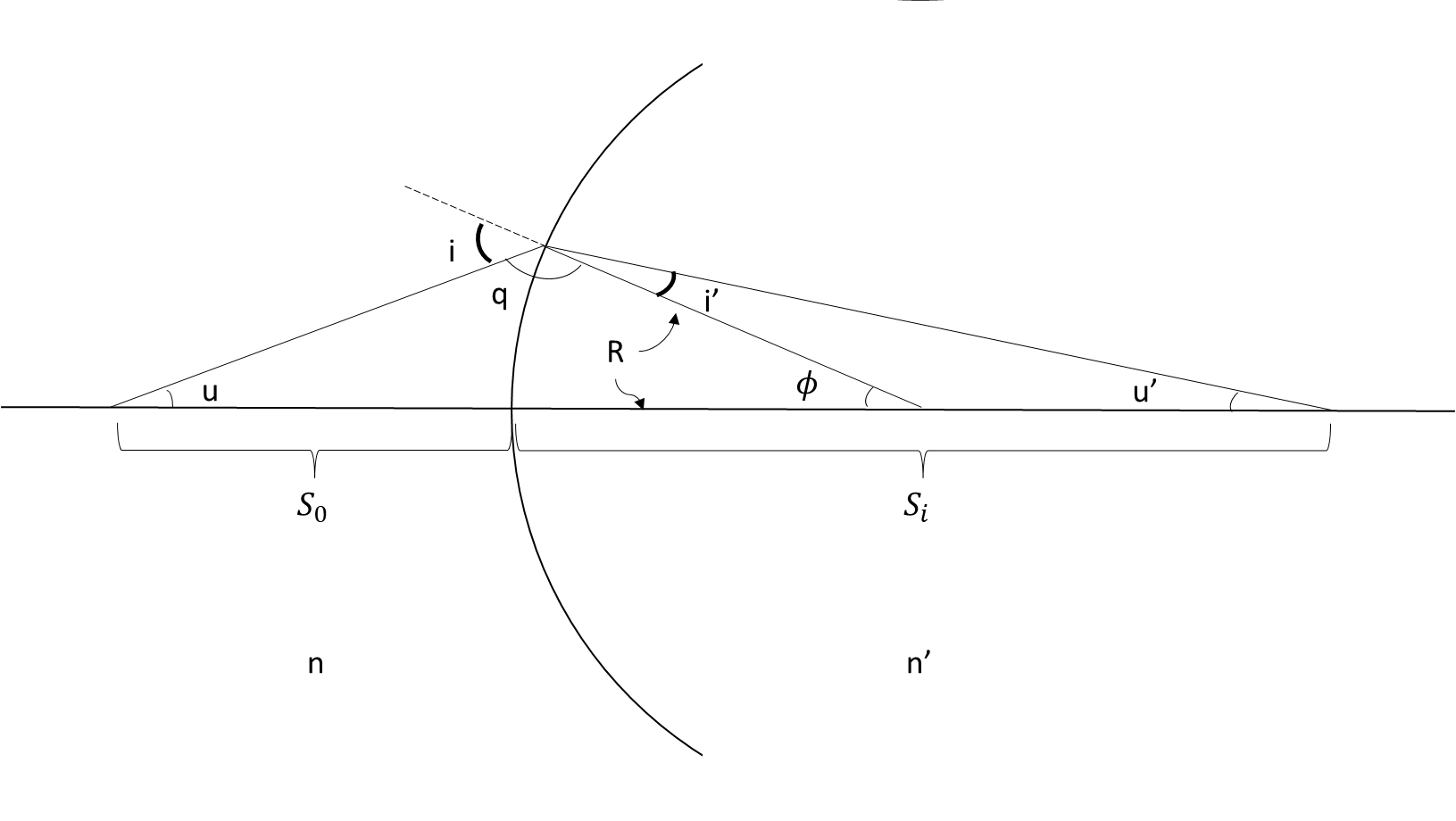

Let’s start by looking at a single spherical surface. We will use Snell’s Law.

Here is our sign convention:

Light travels from left to right

Distances up are positive

Distances to the right are positive

Counterclockwise (CCW) angles are positive

For light travelling right to left, use n as negative.

Single spherical surface interface.

Apply Snell’s Law at the interface:

(4.1)\[\begin{equation}

n \sin (i) = n' \sin (i')

\end{equation}\]

Using the paraxial approximation,

(4.2)\[

n i = n' i'

\]

We need to relate u to i and u’ to i’.

\[\begin{split}

u + \phi + q = 180 \\

q = 180 - u - \phi \\

q + i = 180 \\

i = 180 - 180 + u + \phi \\

|i| = |u| + | \phi | \\

\end{split}\]

From our sign convention, \(u \gt 0\), \(\phi \lt 0\), and \(i \gt 0\). Hence,

\[

i = u - \phi

\]

Next, we’ll relate u’ to i’:

\[\begin{split}

|i'| + |u'| + 180 - |\phi| = 180 \\

|i'| = - |u'| + |\phi|

\end{split}\]

Again, noting that \(i' \gt 0\), \(\phi \lt 0\), and \(u' \lt 0\),

\[

i' = u' - \phi

\]

Substituting into (4.2), we get:

\[

n (u - \phi) = n' (u' - \phi)

\]

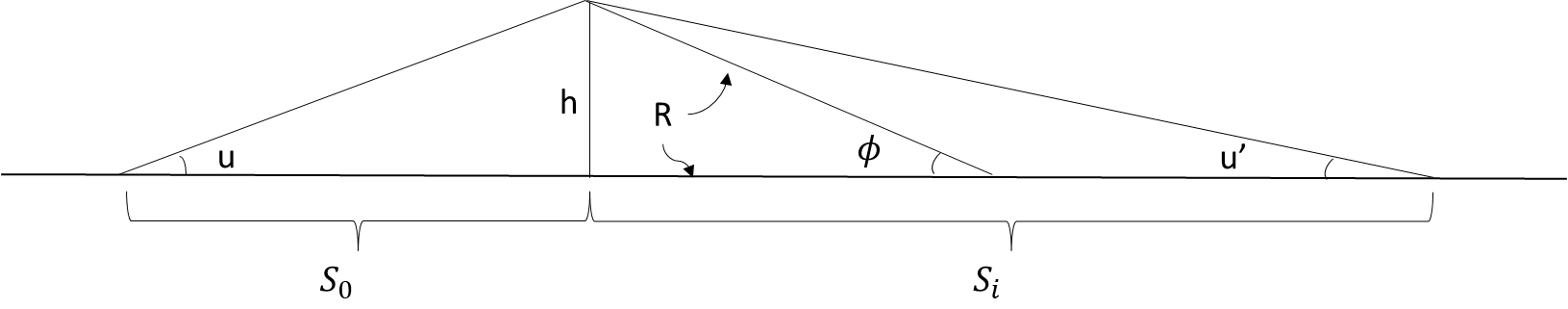

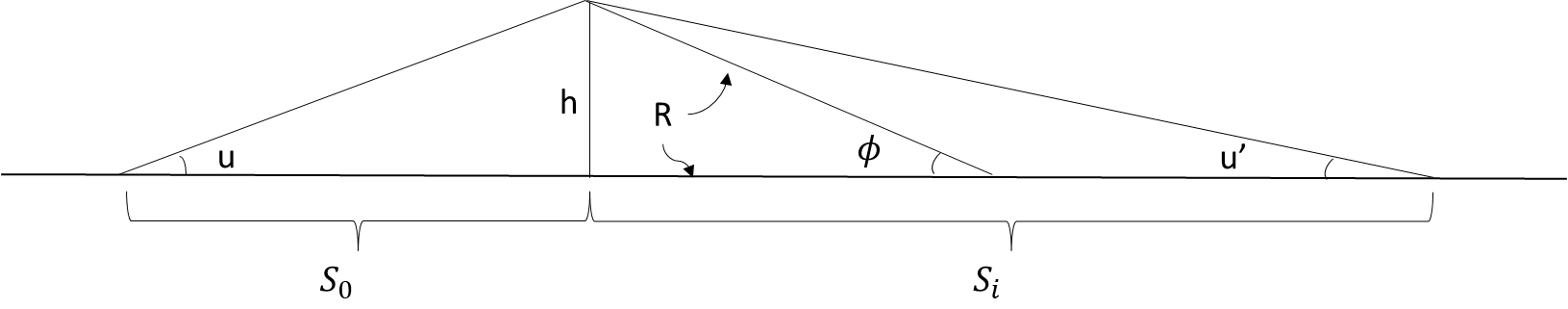

Now, we need to relate the angle equation to position.

Relating angle to position.

Again, using the paraxial approximation,

\[\begin{split}

\tan u \approx u = \frac{h}{S_o} \\

\sin \phi \approx \phi = \frac{h}{R} \\

\tan u' \approx u' = \frac{h}{S_i}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

n (u - \phi) = n' (u' - \phi) \\

n \left( \frac{h}{S_o} - \frac{h}{R} \right) = n' \left( \frac{h}{S_i} - \frac{h}{R} \right) \\

\frac{n}{S_o} - \frac{n}{R} = \frac{n'}{S_i} - \frac{n'}{R} \\

\frac{n}{S_o} - \frac{n'}{S_i} = (n - n') \frac{1}{R} \\

\end{split}\]

Or,

(4.3)\[\begin{split}

\frac{n'}{S_i} - \frac{n}{S_o} = (n' - n) \frac{1}{R} \\

\end{split}\]

where \(1 / R \equiv C\) is the curvature. (4.3) is the

conjugate equation.

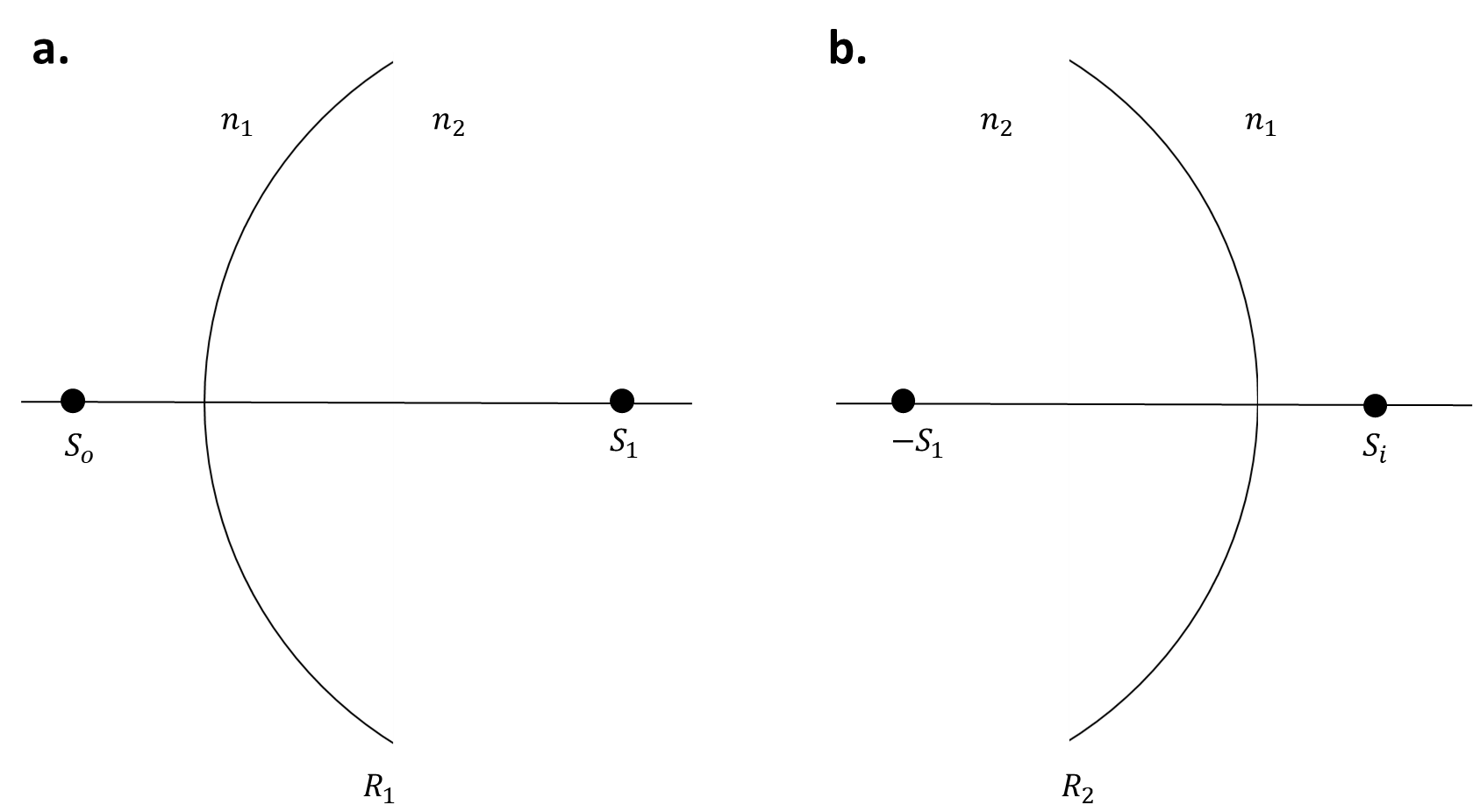

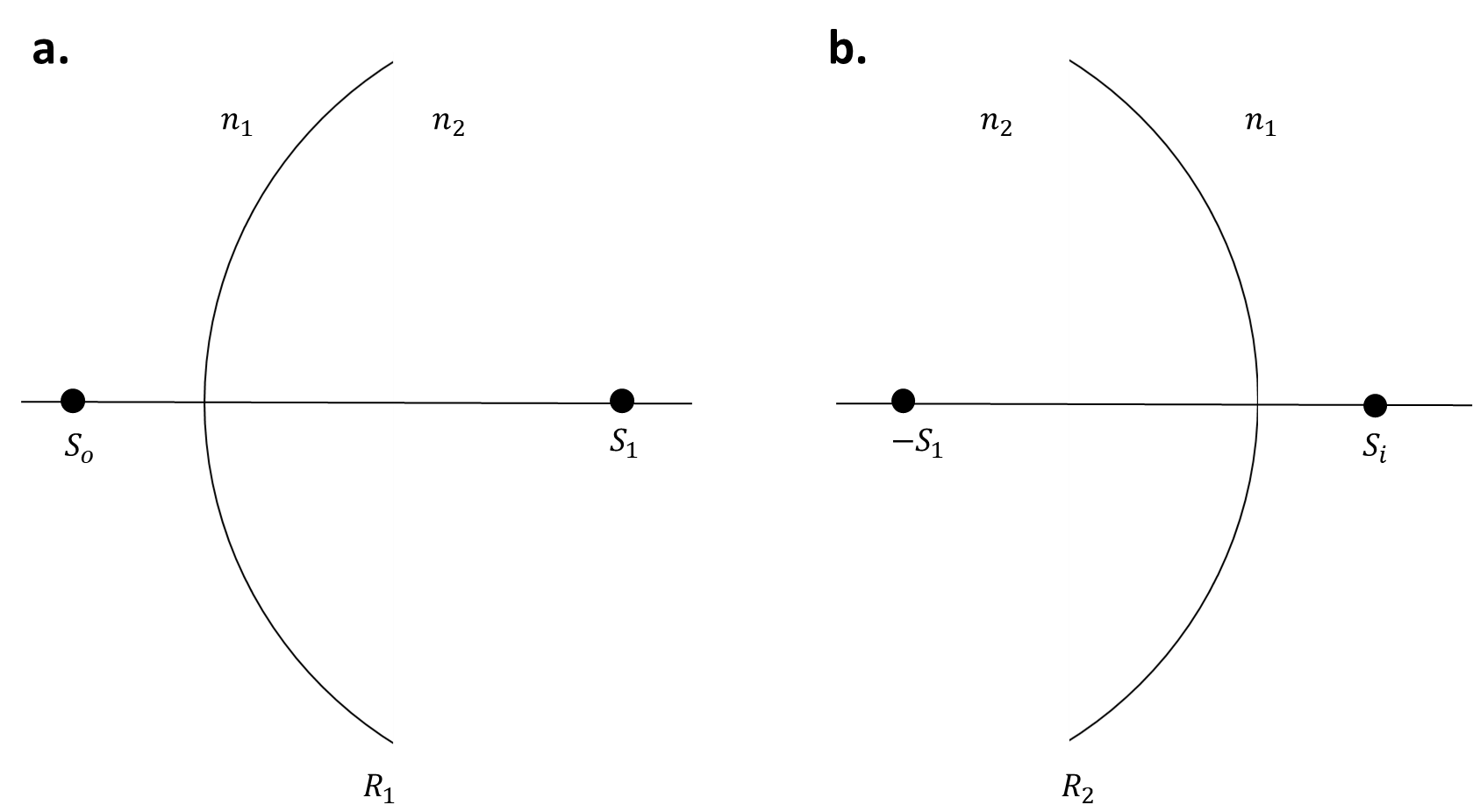

4.2. Thin Lens

We’ll use the conjugate equation for a single surface to get the conjugate

equation for a thin lens.

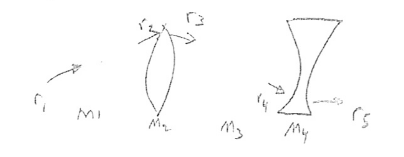

A single surface.

The conjugate equation for the picture in conjugatesurface-fig is:

\[\begin{split}

\frac{n'}{S_i} - \frac{n}{S_o} = \frac{(n' - n)}{R} \\

\end{split}\]

A thin lens.

The thin lens is simply the single surface, replicated; once for entry, and

once for exit. The entry and exit of the material have the same index, with

a different index in the middle. We assume zero separation between lens

surfaces.

A thin lens. a) The first encountered surface. b) The second encountered surface.

The following are true for the first surface:

\[\begin{split}

S = S_o \\

S' = S_1 \\

n = n_1 \\

n' = n_2 \\

R = R_1

\end{split}\]

The conjugate equation for the first surface is

\[\begin{split}

\frac{n_2}{S_1} - \frac{n_1}{S_o} = \frac{(n_2 - n_1)}{R_1} \\

\frac{n_2}{S_1} = \frac{n_1}{S_o} + \frac{(n_2 - n_1)}{R_1}

\end{split}\]

The following are true for the second surface:

\[\begin{split}

S = -S_1 \\

S' = S_i \\

n = n_2 \\

n' = n_1 \\

R = R_2

\end{split}\]

Hence,

\[\begin{split}

\frac{n_1}{S_i} - \frac{n_2}{S_1} = \frac{(n_1 - n_2)}{R_2} \\

\end{split}\]

Substituting \(n_2 / S_i\) from before,

\[\begin{split}

\frac{n_1}{S_i} - \frac{n_1}{S_o} - \frac{n_2 - n_1}{R_1} = \frac{(n_1 - n_2)}{R_2} \\

\frac{1}{S_i} - \frac{1}{S_o} = \left(\frac{1}{n_1}\right) \left( \frac{n_1 - n_2}{R_2} + \frac{n_2 - n_1}{R_1} \right)

\end{split}\]

(4.4)\[

\frac{1}{S_i} - \frac{1}{S_o} = \left(\frac{n_2 - n_1}{n_1}\right) \left(\frac{1}{R_1} - \frac{1}{R_2}\right) = \frac{1}{f}

\]

Remember that distances to the left are negative and distances to the right are positive.

If we define \(S_o\) being left of the lens as “positive”, we get

(4.5)\[

\frac{1}{S_i} + \frac{1}{S_o} = \frac{1}{f}

\]

4.3. Imaging

Now, let’s look at producing an image from an object using a single thin lens.

We will analyze the lens and image using the following properties:

A ray passing through the focal point is bent parallel to the axis of symmetry.

An incident ray parallel to the lens axis is bent to pass through the back focal point.

A ray passing through the center of the lens is unchanged in direction.

A point in the object space is imaged to a point in the image space.

Parallel rays image to a point (a lens converts from incident angle to a point).

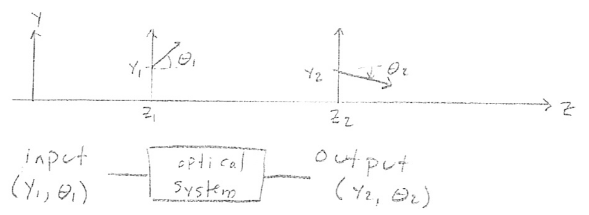

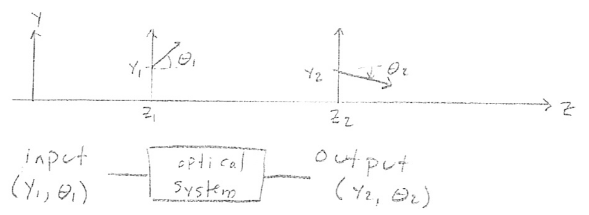

4.5. ABCD Matrices

In a homogeneous material, rays travel in straight lines. A ray is

characterized by its position and direction.

An optical system is a set of optical components that change the position and

direction of rays.

In the paraxial approximation, when all angles are sufficiently small so that

\(\sin \theta \approx \theta\), the relationship between \((y_2, \theta_2)\) and

\((y_1, \theta_1)\) is linear.

\[\begin{split}

y_2 = A y_1 + B \theta _1 \\

\theta _2 = C y_1 + D \theta _1 \\

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

\begin{bmatrix}

y_2 \\

\theta _2

\end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix}

A & B \\

C & D

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

y_1 \\

\theta _1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

The matrix

\(M = \begin{bmatrix}

A & B \\

C & D

\end{bmatrix}\)

characterizes the optical system.

Let’s calculate the ABCD matrices of some common components.

4.5.1. Free-Space Propogation

Rays travel in straight lines.

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

y_2 &= y_1 + \theta _1 d \\

\theta _2 &= \theta _1

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

M =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & d \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

4.5.2. Refraction at a Planar Boundary

\[

y_2 = y_1

\]

From the conjugate equation:

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

n (\theta _1 - \alpha) &= n' (\theta _2 - \alpha) \\

\alpha &= \frac{y_1}{R} \\

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

n \theta _1 - \frac{n}{R} y_1 &= n' \theta _2 - \frac{n'}{R} y_1 \\

\theta _2 &= \frac{n' - n}{n' R} y_1 = \frac{n}{n'} \theta _1 \\

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

M =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

\frac{n-n'}{n' R} & \frac{n}{n'}

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

4.5.3. Thin Lens

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

y_2 &= y_1 \\

\theta _2 &= \theta _1 - \frac{y_1}{f}

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

M =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

- \frac{1}{f} & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

4.5.4. Reflection from a Planar Mirror

\[\begin{split}

M =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

4.5.5. Reflection from a Spherical Mirror

\[\begin{split}

M =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

\frac{2}{R} & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

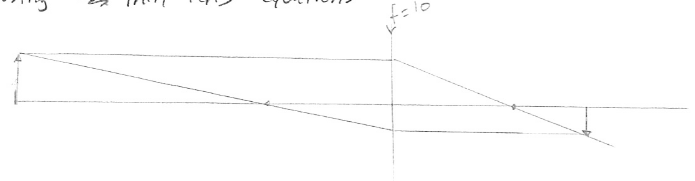

4.6. Multiple Elements

Multiple elements demonstrating ABCD matrix multiplication.

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

r_2 &= M_1 r_1 \\

r_3 &= M_2 r_2 = M_2 M_1 r_1 \\

r_4 &= M_3 r_3 = M_3 M_2 M_1 r_1 \\

r_5 &= M_4 r_4 = M_4 M_3 M_2 M_1 r_1 \\

M_{tot} &= M_4 M_3 M_2 M_1

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

The first element encountered by the ray is the last matrix in the

multiplication (since matrix multiplication is performed right to left).

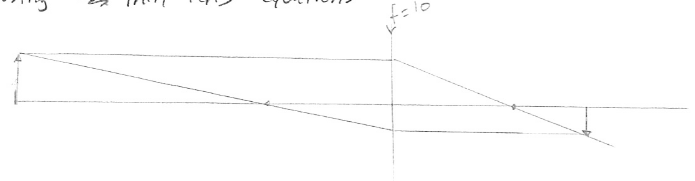

Example: Multiple lenses

Find the image location and magnification.

\(S_0 = 30mm\)

\(d = 5mm\)

\(f_1 = 10mm\)

\(f_2 = -20mm\)

Solution

First lens analysis.

Using the thin lens equations,

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

\frac{1}{30} + \frac{1}{S_{i1}} &= \frac{1}{10} \\

S_{i1} &= \left( \frac{1}{10} - \frac{1}{30} \right) ^{-1} = 15 \\

M_1 &= - \frac{S_{i1}}{S_{o1}} = - \frac{15}{30} = - \frac{1}{2}

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

Second lens analysis.

Adjusting \(S_{o2}\) to be relative to the second lens, which is 5 mm in front

of the first lens,

\[

S_{o2} = 15 - 5 = -10

\]

we get,

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

\frac{1}{-10} + \frac{1}{S_{i2}} &= - \frac{1}{10} \\

S_{i2} &= \left( - \frac{1}{20} + \frac{1}{10} \right) ^{-1} = 20 \\

M_2 &= \frac{-20}{-10} = 2

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

\[

M = -\frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 = -1

\]

The magnification is unity (although the image is inverted) and the image is

20 mm to the right of the second lens.

Example: ABCD matrices with multiple lenses

Repeat the last example, but using ABCD matrices.

Solution

The distance to the first lens is:

\[\begin{split}

M_1 =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 30 \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

The first lens is:

\[\begin{split}

M_2 =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

- \frac{1}{10} & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

The distance from the first to the second lens is:

\[\begin{split}

M_3 =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 5 \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

The second lens is:

\[\begin{split}

M_4 =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

\frac{1}{20} & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

The distance to the focus is:

\[\begin{split}

M_5 =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & d \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{split}\]

If we launch a ray with a height of 1 and a variable ray angle into the system,

we get:

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

\begin{bmatrix}

y_2 \\

\theta _2

\end{bmatrix}

&=

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & d \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0.05 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 5 \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

-0.1 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 30 \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 \\

\theta

\end{bmatrix} \\

&=

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & d \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

0.5 & 20 \\

-0.075 & -1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 \\

\theta

\end{bmatrix} \\

&=

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & d \\

0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

0.5 & 20 \theta \\

-0.075 & -\theta

\end{bmatrix} \\

\begin{bmatrix}

y_2 \\

\theta _2

\end{bmatrix}

&=

\begin{bmatrix}

0.5 + 20 \theta + d(-0.075 - \theta) \\

-0.075 - \theta

\end{bmatrix}

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

For an image point, the ray height needs to be independent of the incident ray

angle.

\[

y_2 = 0.5 - 0.075 d + (20 - e) \theta

\]

where

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align}

20 - d &= 0 \\

d &= 20

\end{align}

\end{split}\]

Back substitute \(d = 20\) to get the image height:

\[

y_2 = 0.5 - (0.075)(2) = -1

\]

We get the same result; namely, the object location is 20mm to the right of the

second lens and the magnification is -1.